$ 50 PURCHASE NOW

-

"This book is as essential as it is beautiful. It belongs on the shelf of every tree hugger, to understand the loggers who cherish our forests too – and to remind all of us of the precious in the everyday. Every tree matters. So does every person. The wood products we all use come from somewhere, and are made by someone. In this remarkable book, David Paul Bayles reminds us of the essential connections between people and the land and the products we use, too often without thinking or appreciation.”

—Lynda Mapes, Environmental Writer Seattle Times, Author of The Trees are Speaking: Dispatches from the Salmon Forests, and The Witness Tree

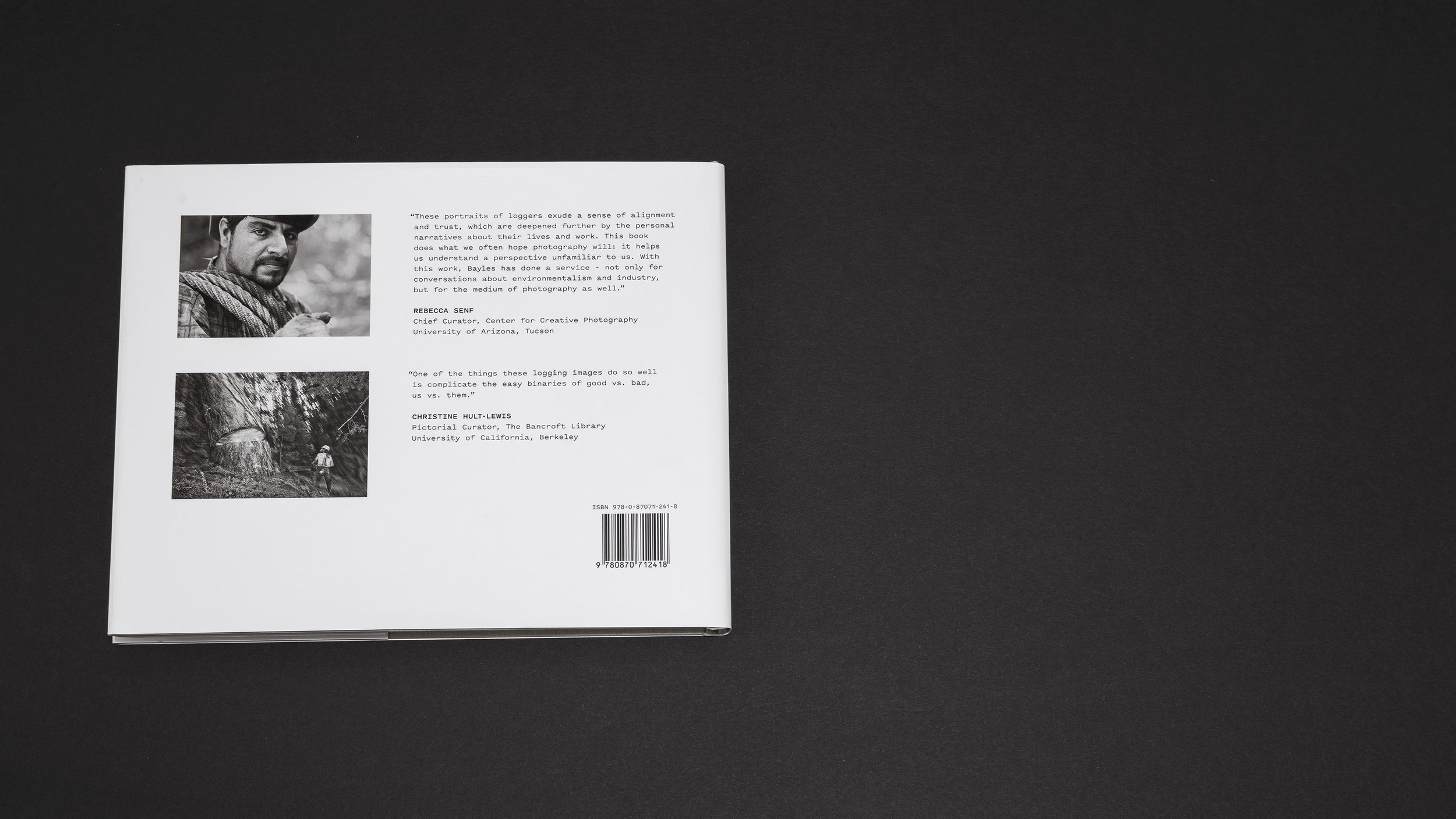

“These portraits of loggers exude a sense of alignment and trust, which are deepened further by the personal narratives about their lives and work. This book does what we often hope photography will: it helps us understand a perspective unfamiliar to us. With this work, Bayles has done a service - not only for conversations about environmentalism and industry, but for the medium of photography as well.”

—Rebecca Senf, Chief Curator, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Tucson

“The opening sequence of trees being felled provides a stunning, wordless way to better understand the portraits and stories that follow. Despite the dangers they faced daily, the men loved the work, the woods, their families, and each other—and this is made beautifully plain to see in David's images and sparse, poignant writing.”

– James G. Lewis, Historian, Forest History Society, Duke University, Durham

“One of the things these logging images do so well is complicate the easy binaries of good vs. bad, us vs. them.”

— Christine Hult-Lewis, Pictorial Curator, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

“These portraits of loggers are deeply human and the Falling Tree images are unique in the history of photography.”

— Roy Flukinger, Photographic Historian, Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas, Austin

-

THE HARDER THEY FALL

Logging is inextricably woven into the fabric of the Pacific Northwest. And while the timber industry is in decline today for a variety of reasons, it remains an important economic driver across the region and has left an indelible cultural imprint on the people who live here.

A new book by photographer David Paul Bayles offers an insightful perspective on an industry that has done more than perhaps any other to shape both the landscapes and the people in this part of the world.

Bayles, who now makes his home in Philomath, spent four years in the 1970s working on a northern California logging crew before pursuing his dream of going to art school to study photography. The following decade, he went back into the woods to document the lives of loggers with his camera, creating a traveling exhibition that was shown in museums in California and Oregon. In 2004, he pushed the boundaries of the project still further, focusing on how mechanization was transforming the industry, robbing it of much of its human element.

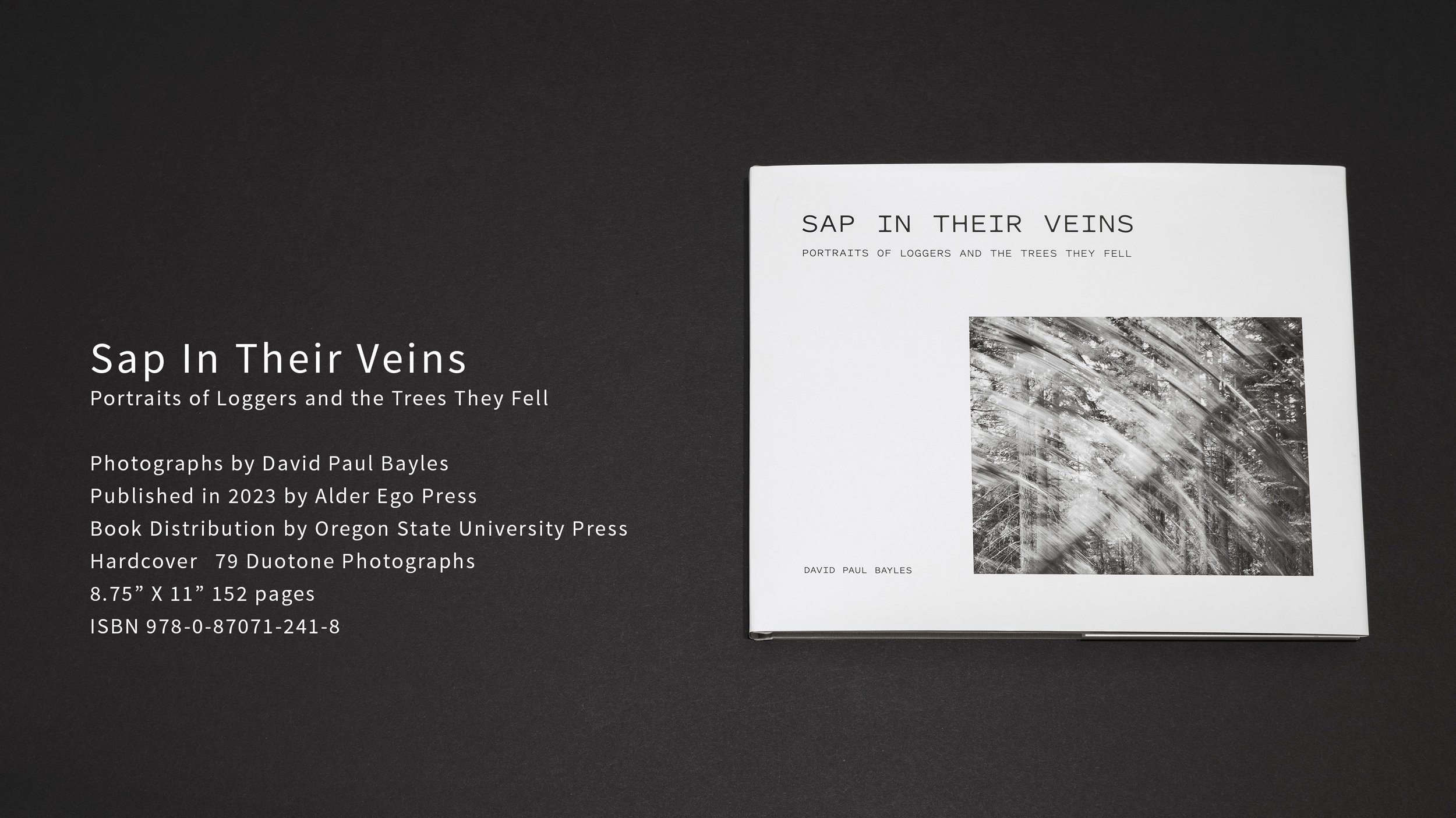

With “Sap in Their Veins: Portraits of Loggers and the Trees They Fell,” Bayles distills and transforms his earlier work into a beautifully printed coffee table book.

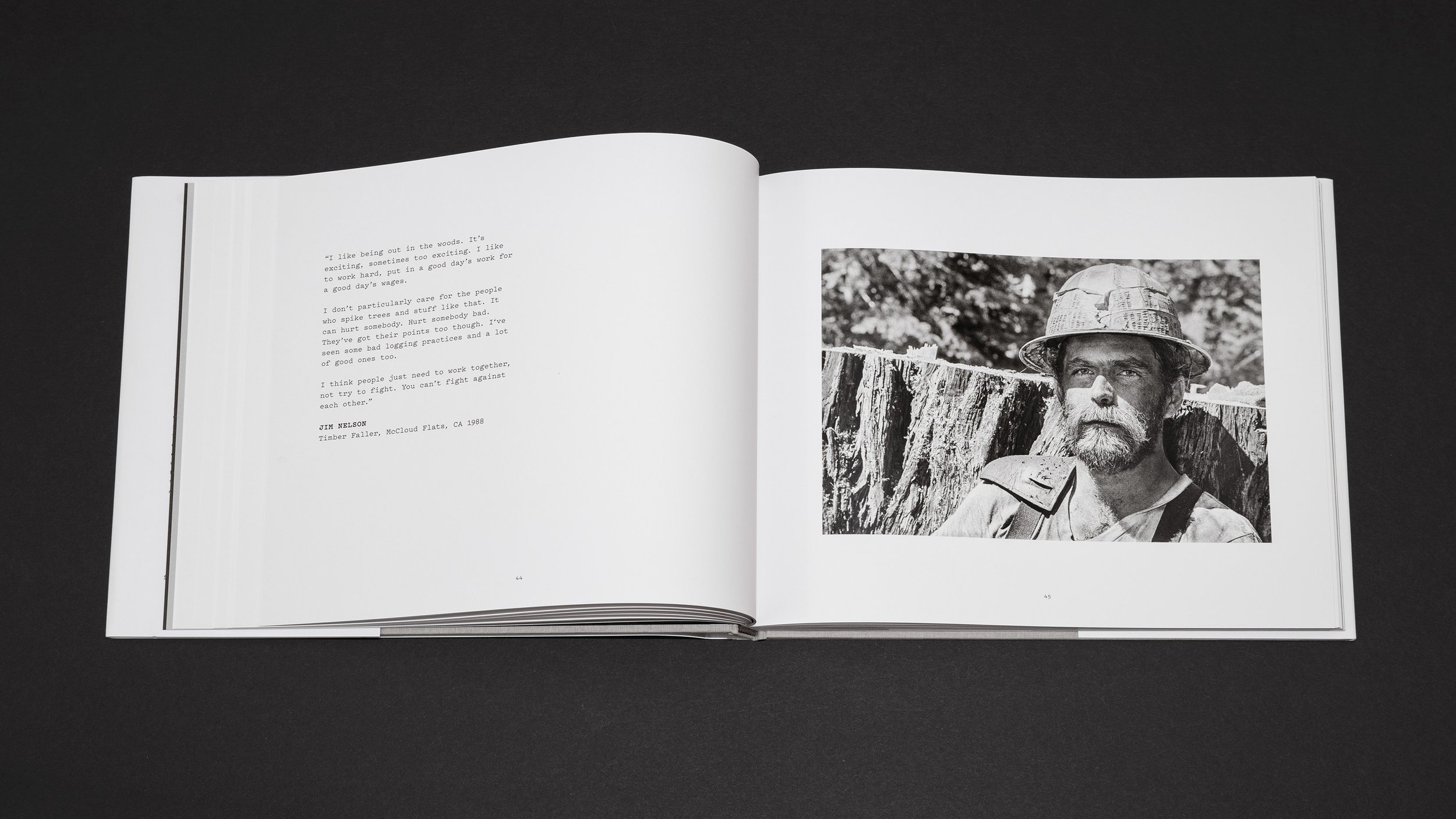

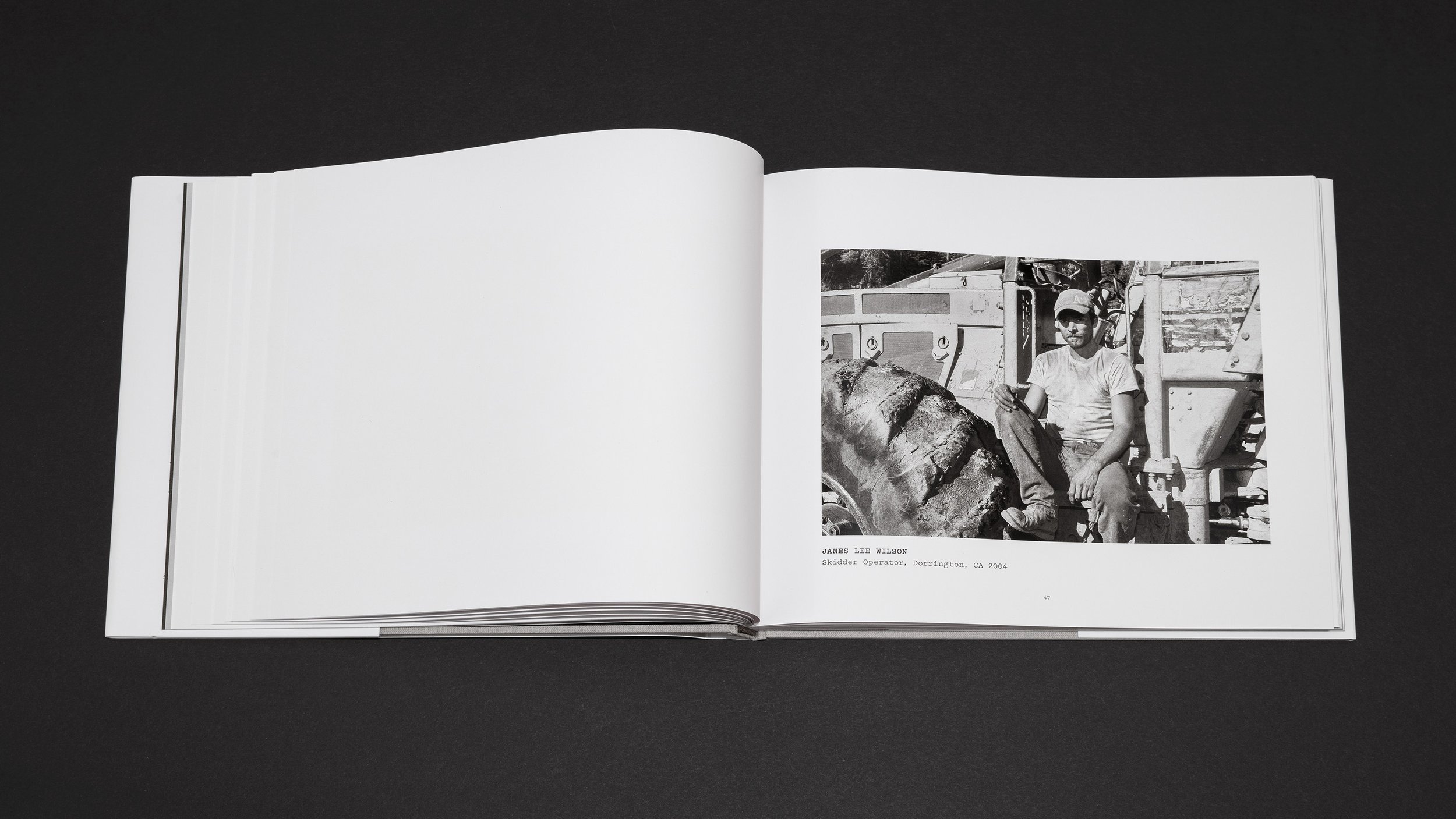

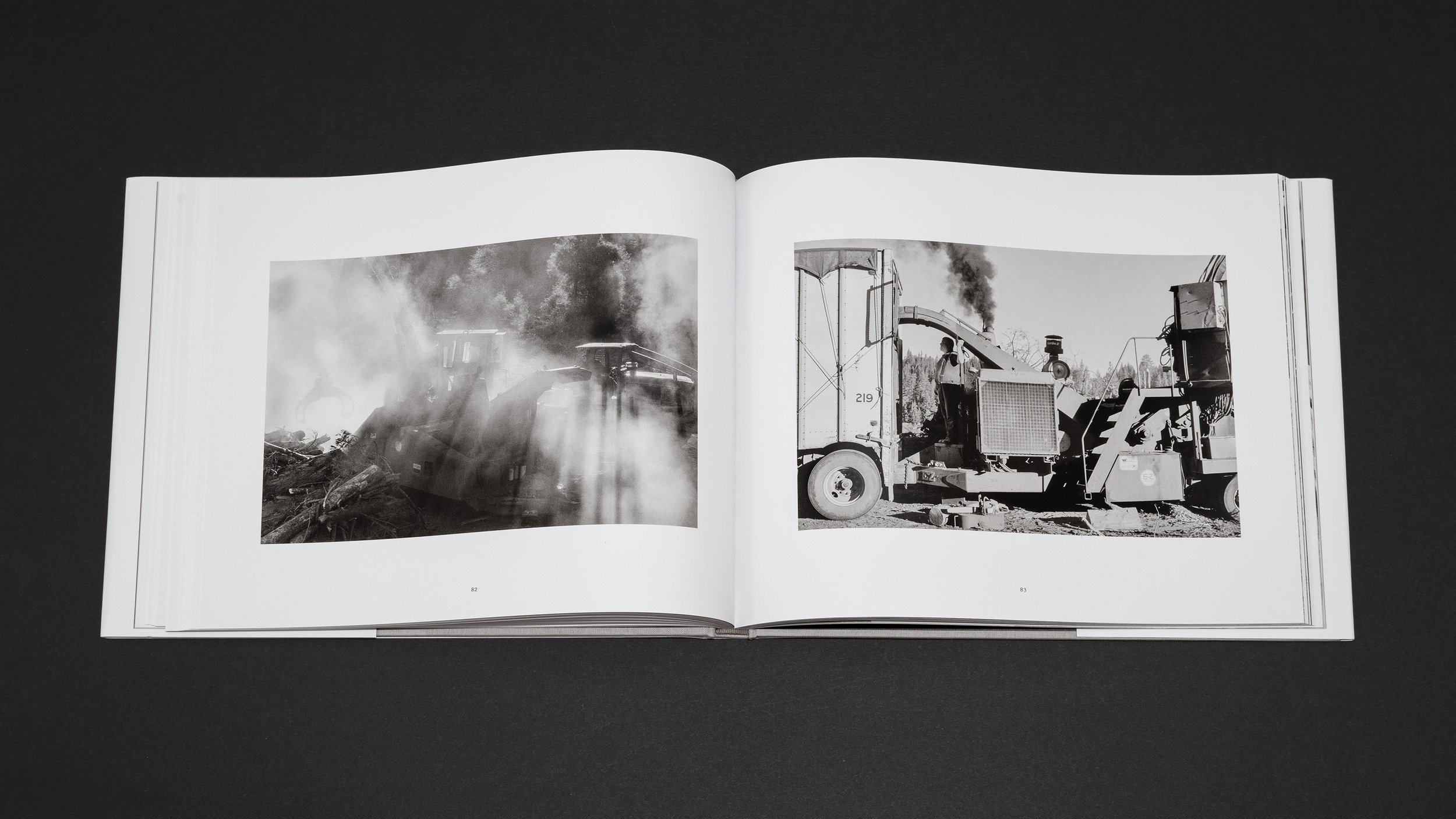

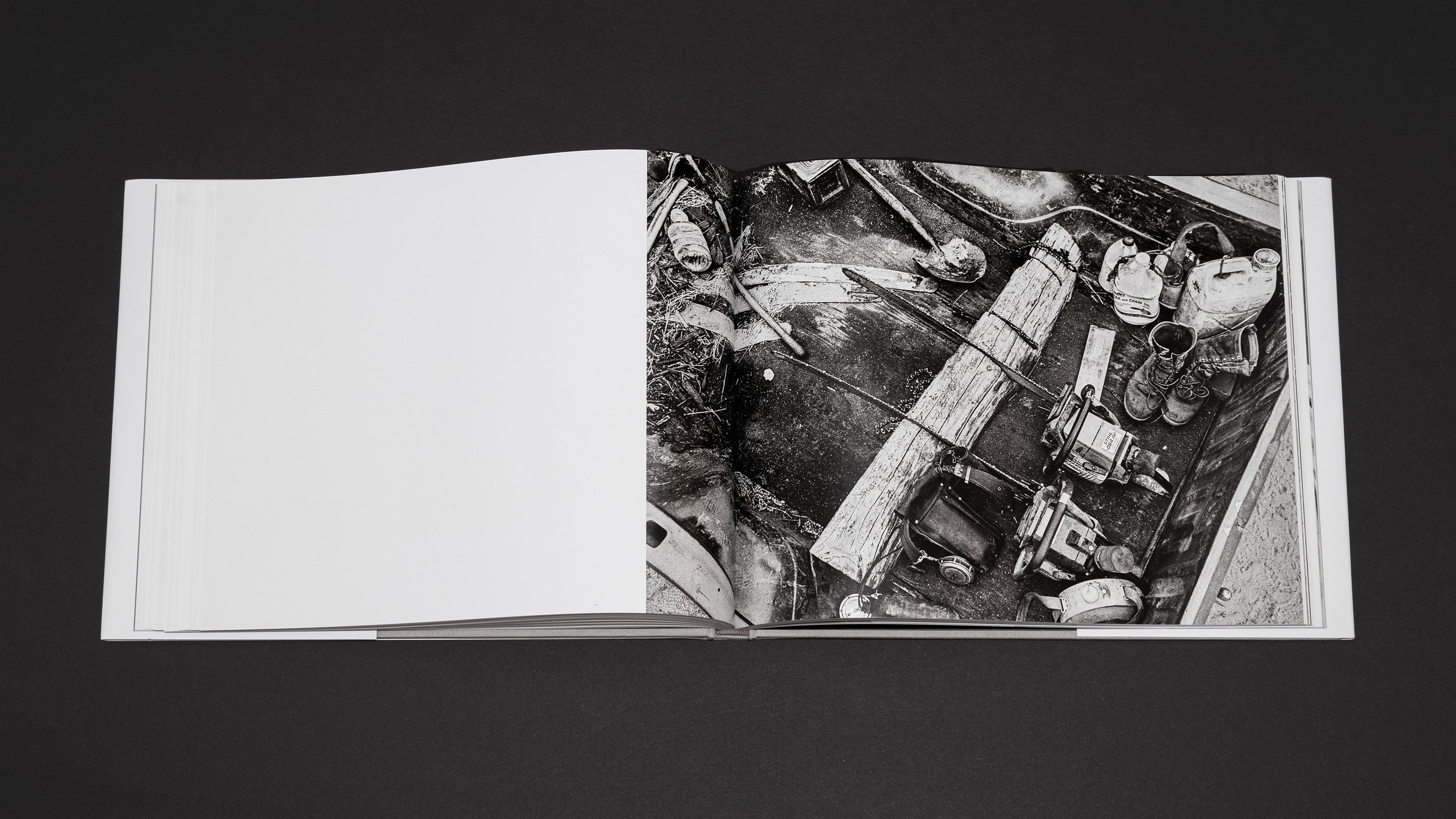

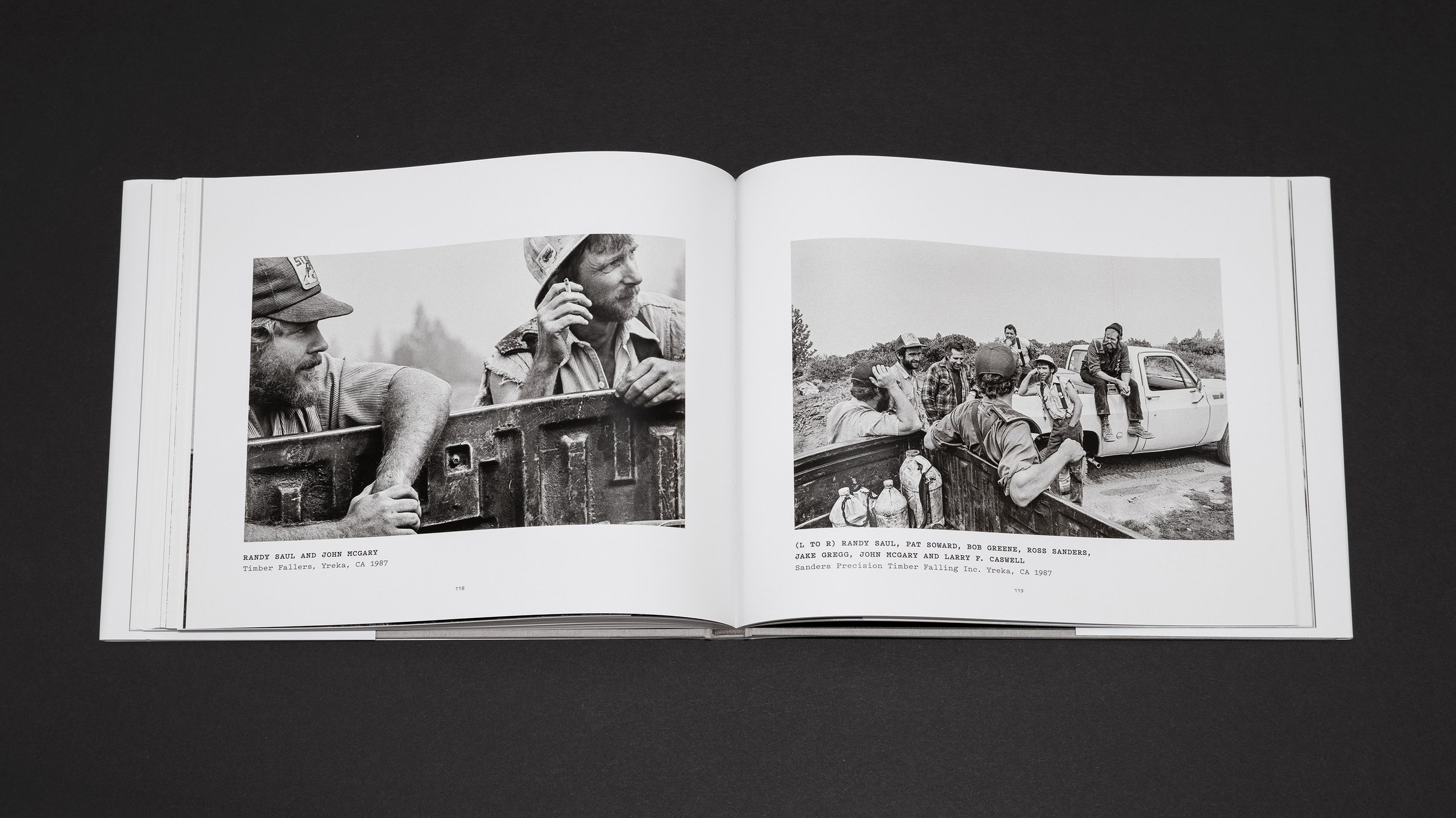

Anchored by 79 powerful black-and-white photographs, the book also features a preface and several short essays by the author, as well as excerpts from oral history interviews with a colorful cast of timber fallers, choker setters, knot bumpers and cat skinners. (There’s also a glossary that explains these and other logging terms for the uninitiated.)

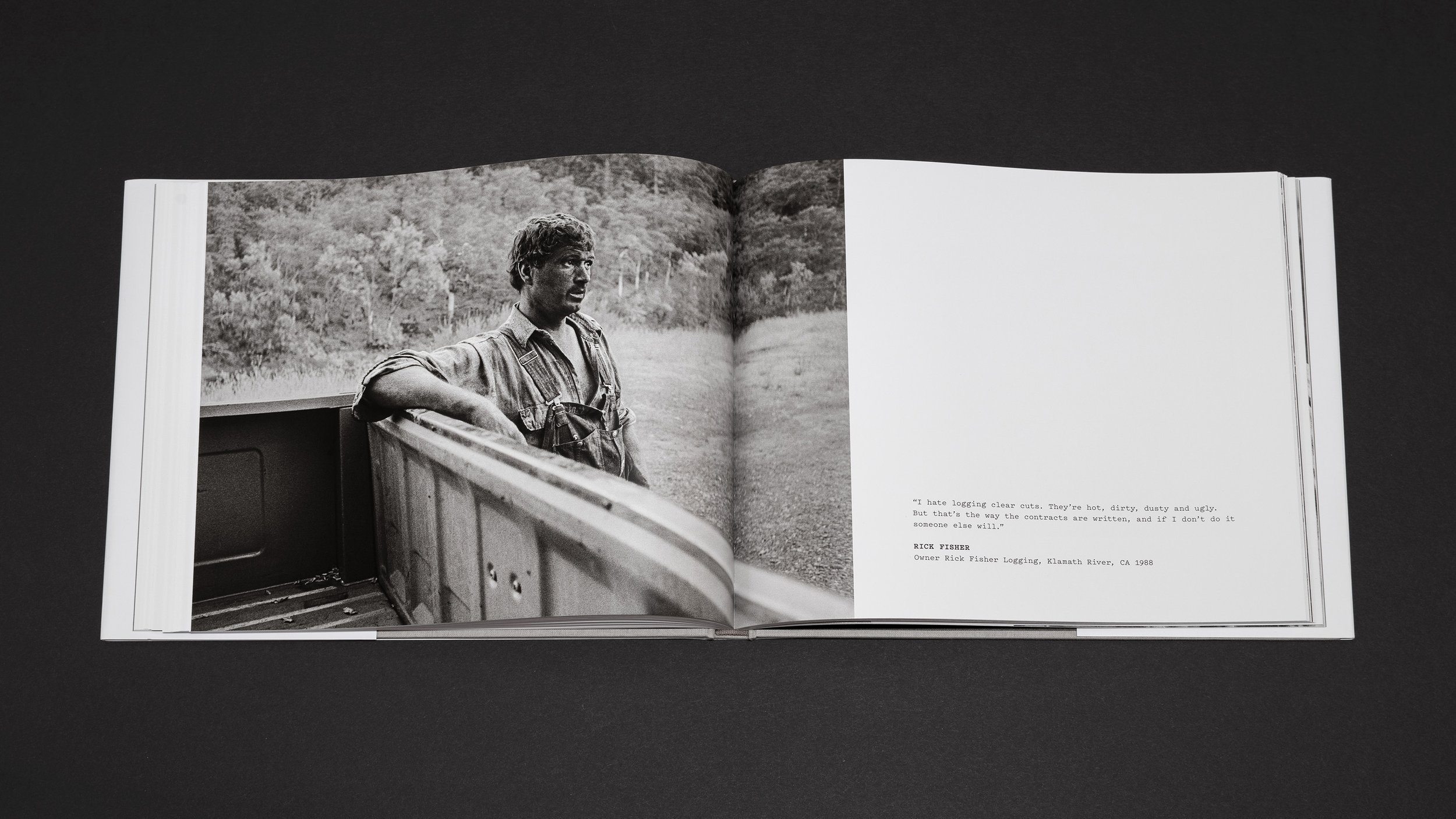

The book steers clear of environmental politics, maintaining a sense of clear-eyed objectivity as it documents the work of logging as practiced in the Northern California forests in the 1980s and the now-vanishing way of life that went along with it.

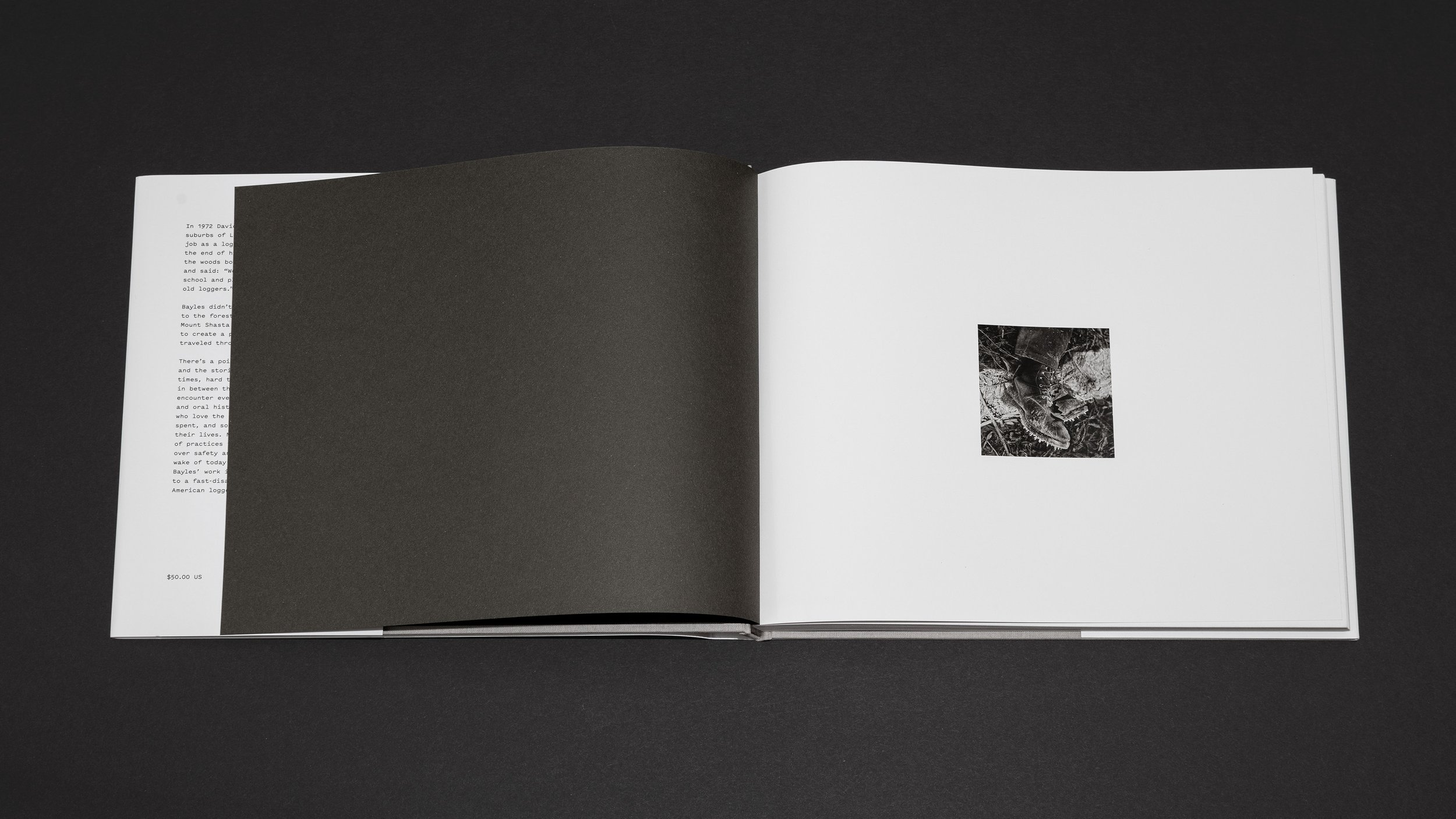

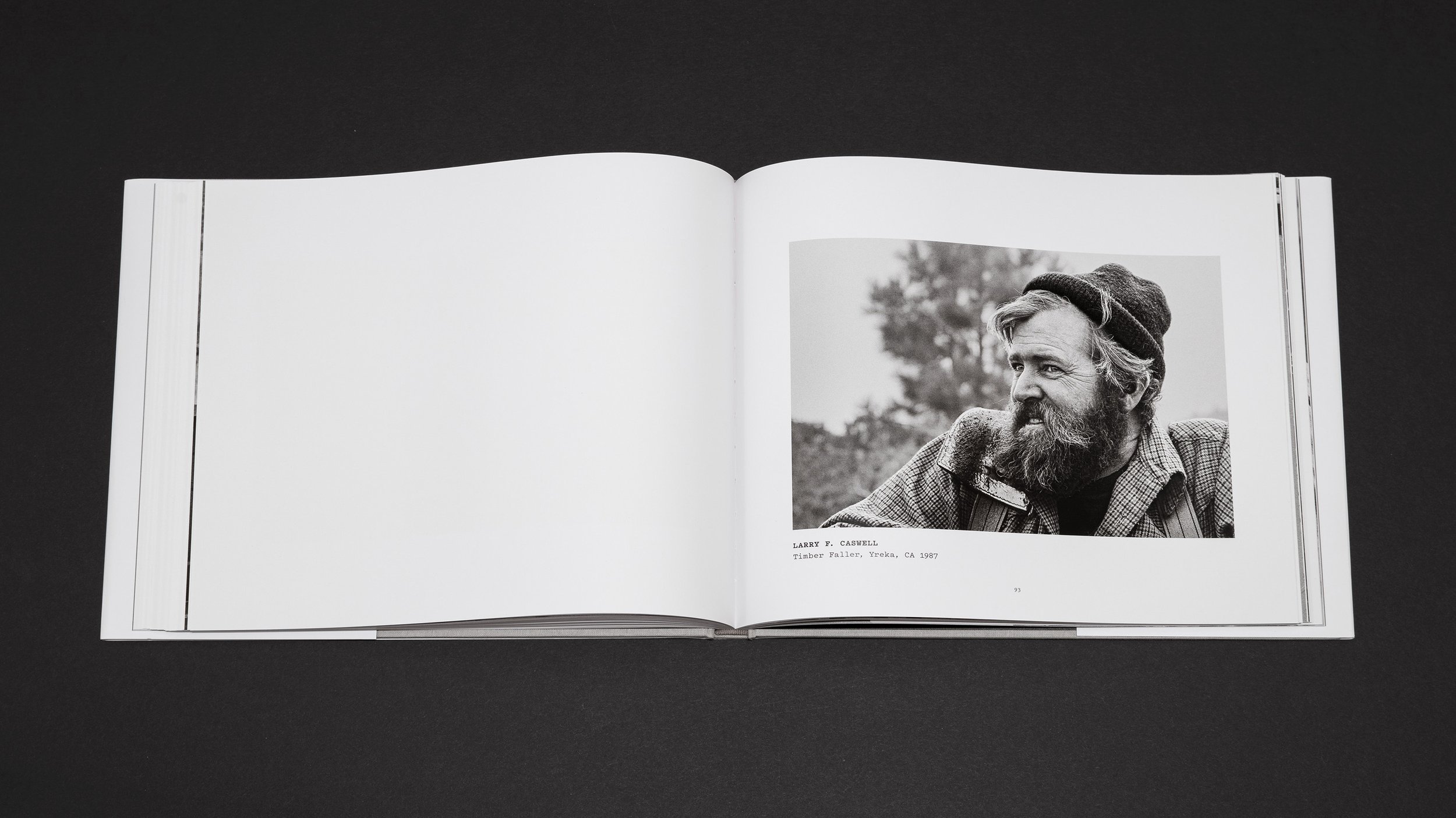

The portraits of men at work in the woods call to mind the Depression-era photographs of Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans as Bayles captures both the gritty details of a difficult and dangerous profession and the essential human dignity of his subjects.

Bayles’ brief essays and the words of the loggers themselves paint a compelling picture of rugged, hardworking men who also feel a profound connection with the forests where they ply their trade.

“Loggers are very concerned about the woods and environment,” said Ross Sanders of Sanders Precision Timber Falling in McCloud Flats, California. “We make our living there and love the woods and timber in such a deep way that I doubt I could ever describe it to you or anyone. Yes, we are in it to make money, and yes, I want to do well, but I also want to ensure a future for my sons should they make the decision to spend all or part of their life in the woods.”

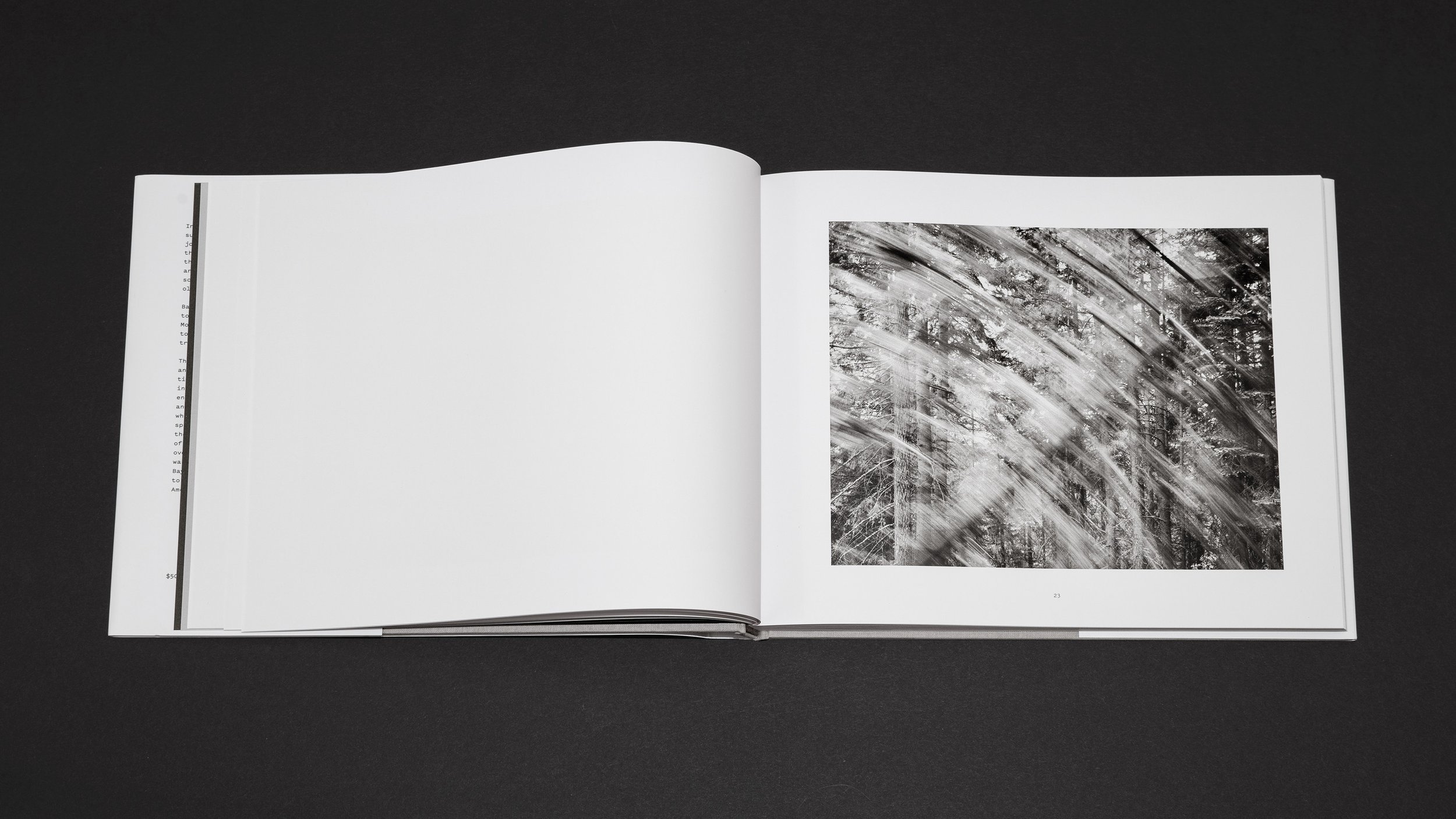

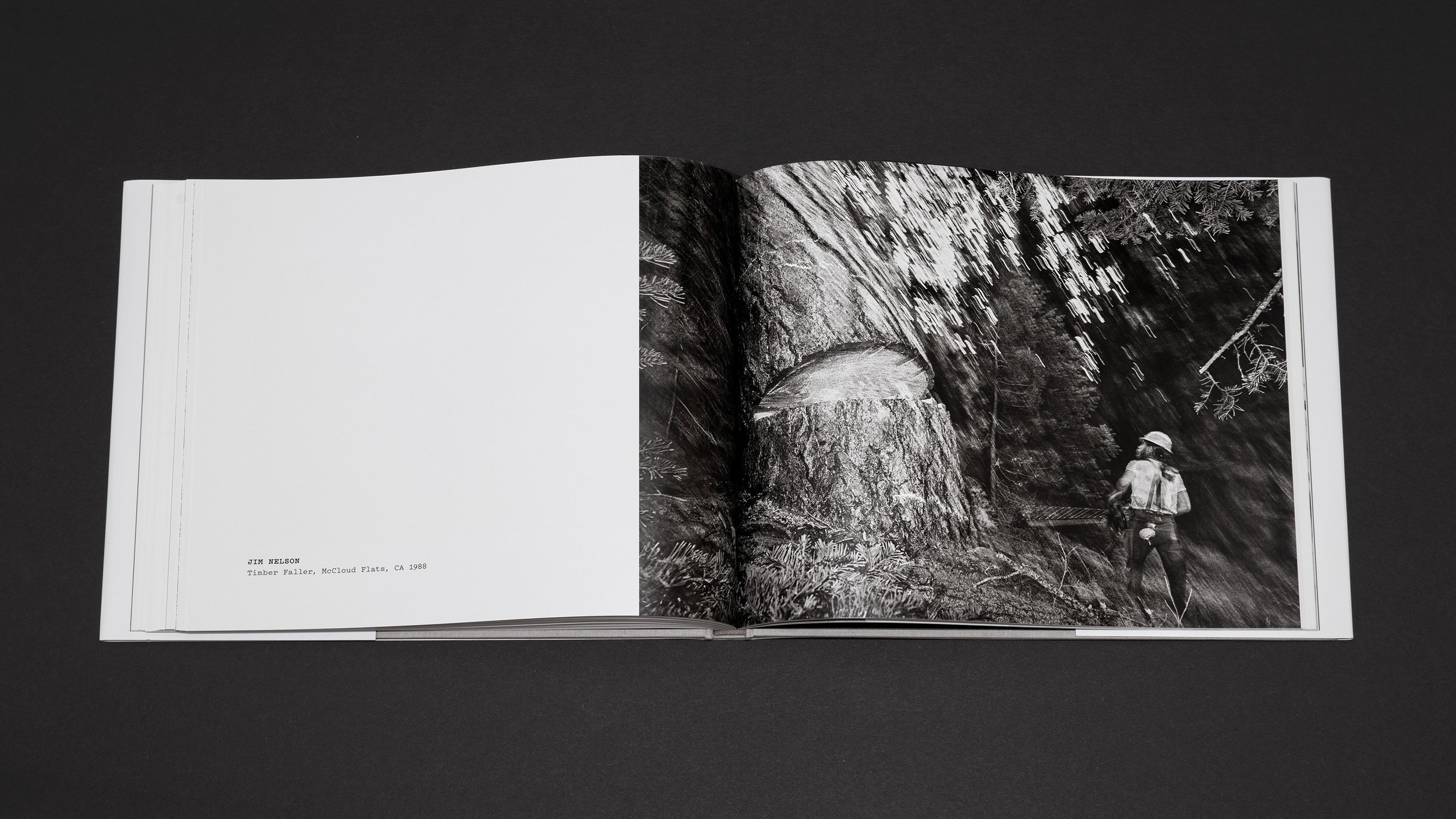

What really sets this book apart, though, are the portraits of falling trees.

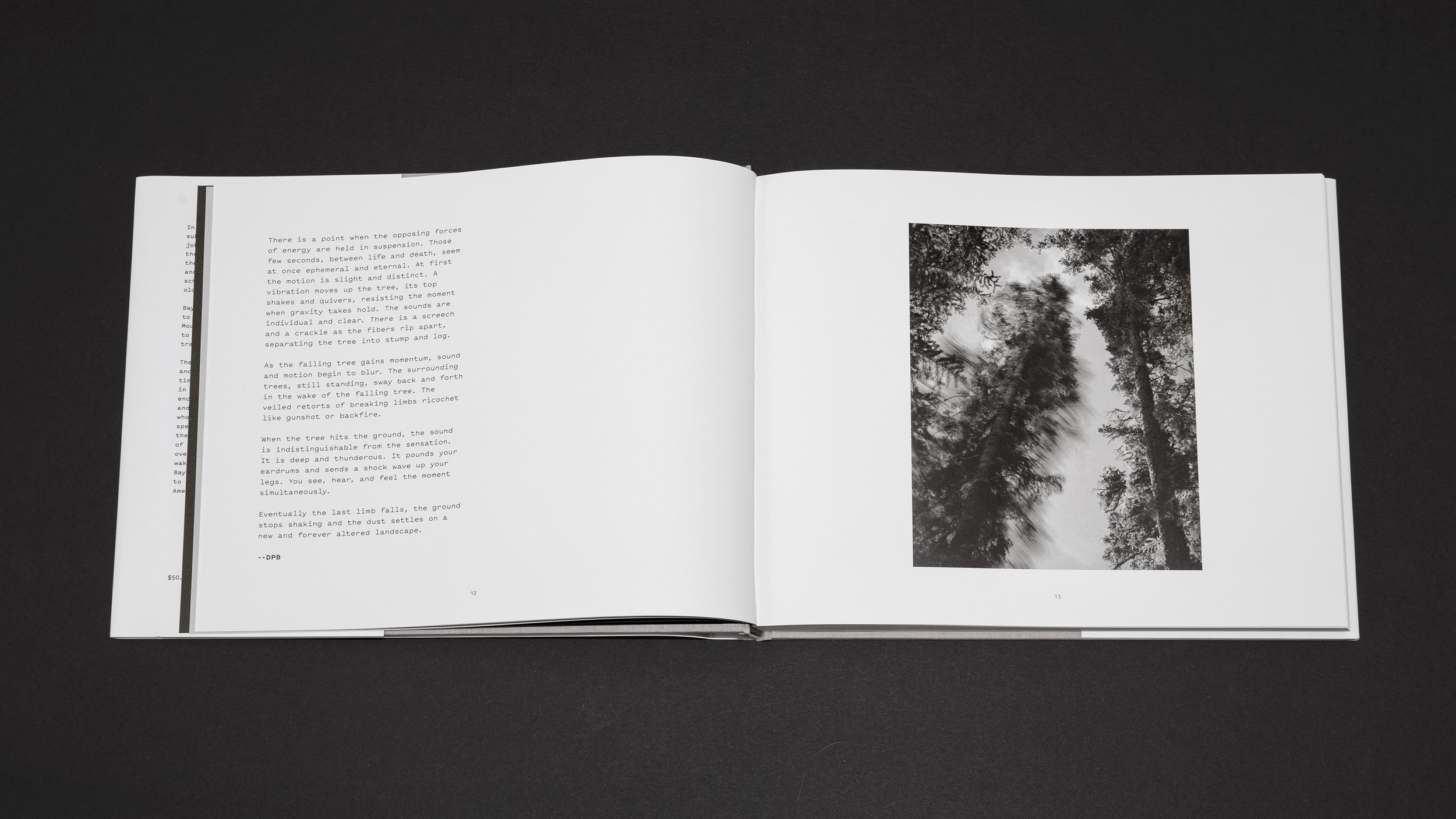

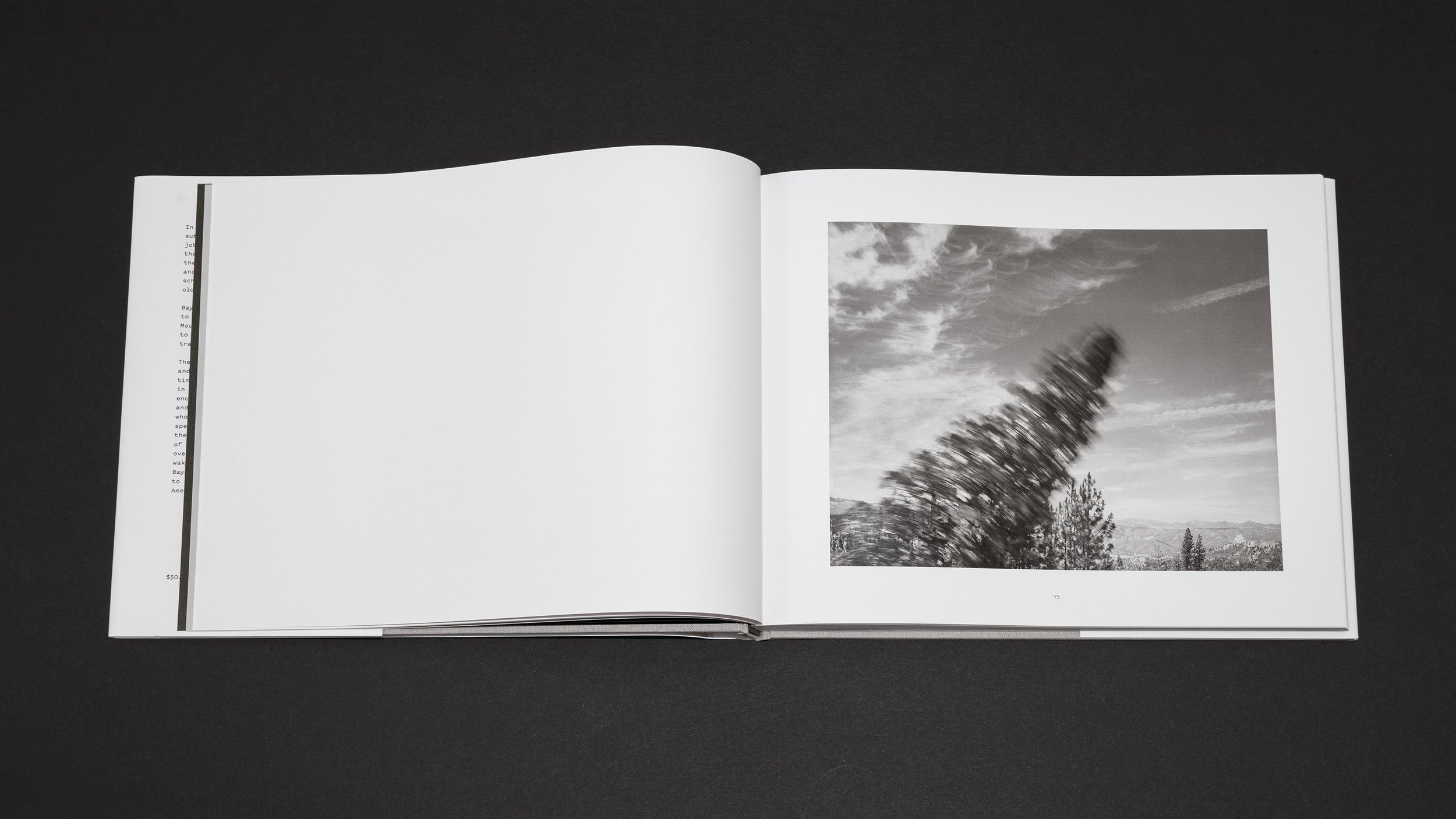

Through the deft use of motion blur, Bayles captures these forest giants in the very act of crashing to the ground, creating a sense that we are witnesses to the final moments of their lives. We see the swift yet ponderous motion of the tree’s downward arc, the wild whip of the flailing branches, the rain of needles falling from the sky and the plume of dust that rises upward after the trunk’s thunderous impact with the earth.

In a short, incisive essay, Bayles describes what it’s like to be present in that moment.

“There is a point when the opposing forces of energy are held in suspension,” it begins. “Those few seconds, between life and death, seem at once ephemeral and eternal.”

The final two frames in this set form a before-and-after diptych, showing a mature tree towering majestically over a forest glade and that same space in the woods after the tree is gone.

There are no humans in this set of images, which has the effect of giving the trees a value separate from, yet equal to, the loggers who harvest them. After reading this book, one suspects most of these loggers wouldn’t have a problem with that.

— Bennett Story Hall, GO! Eastern Oregon

-

Sap in Their Veins offers portraits of loggers as well as their personal narratives. Photographer David Paul Bayles was able to document loggers as an insider, as he himself spent four seasons working in the woods with logging crews. Looking at and reading the book we develop a better understanding of loggers and of how they view their job, its traditions and evolution, and as a result we do not see them as one-dimensional cartoon characters but as distinct and complex individuals.

The photographs were taken in the late 1980s during the spotted owl controversy and then again in the mid-2000s. Besides the author’s preface, a logging glossary, and acknowledgements, the book has two distinct parts. In the opening “Falling Trees” section the photographs to my mind function as art and in the second “Portraits and Stories” section they function as photojournalism. But they share the same focus and complement each other.

In the “Portraits and Stories” section the photographs work to tell a story about loggers, while in the “Falling Trees” section the photographs have no story-telling responsibilities but can resonate freely on a factual as well as a metaphorical level. It is just the trees falling – the thing itself – with no one telling the viewer what to think. Here there is no text but just a series of sixteen photographs, mostly one to a page.

The sixteen images stand as powerful testimony to the pathos, banality, and violence of cutting down trees. Although they (and the book) are agnostic as to whether cutting trees is harvesting or senseless killing, the photographs document the irreversible moment between the Before and After, between existence and nothingness. This is high drama, and great art. Death in the afternoon, but in the forests of California. Bruegel’s Fall of Icarus, where nobody pays attention to the unfolding tragedy, and where life goes on as before.

The tension between life and death is memorably rendered in the liquid blurs that registered movement on the film as it was exposed – the perfect visual metaphor for the final transition between dimensions, made even more vivid as in Bruegel by the contrast with the highly detailed, picture-perfect natural surroundings. Wow. These are deceptively simple photographs with timeless as well as contemporary resonance, and they offer a singular contribution to American landscape photography.

The second section, “Portraits and Stories,” is more extensive and documents the men and machines in words and pictures. We see and hear from fallers, choppers, chipper operators, catskinners, choker setters, knot bumpers, siderods, hook tenders, feller bunchers, loader operators, truck drivers, and tanbark peelers. We see them in action working in the woods, resting on lunch break, relaxing with their crewmates at the end of the day, and at home with their kids.

A behind-the-scenes view of a little-known profession, Sap in Their Veins offers a unique, well-documented look at loggers and logging.

____________

Hans Hickerson, Associate Editor of the PhotoBook Journal, is a photographer and photobook artist from Portland, Oregon.

-

Deeper Look from a Sharp Eye

This book is a tribute to hard-scrabble practitioners with hard-won job titles and jargon in a fast-fading era in American history.

Photographer David Paul Bayles left L.A. in his youth for a summer job as a logger that clearly impacted his soul in a caring way, inspiring him to go back, re-examine and share his love of the land and respect for the trade, with new, wide-ranging perspectives on a business much maligned despite the continued high demand for lumber.

The result is an outstanding insider's view from the heart of old-growth forests, with portraits of men and the trees they fell, storytelling from the boots on the ground, with and on behalf of loggers and an ancient practice transformed by modern machinery in the 21st century.

—Pepper Pro, Tree Link, December 15, 2024

-

In 1972 David Paul Bayles left the suburbs of Los Angeles for a summer job as a logger. Then, instead of heading off to photography school in the fall as planned, he stayed. Four years later, celebrating the end of his last day of logging with his crewmates over a few beers, the woods boss toasted him: “We wish you well in photo school and please don’t forget us dirty old loggers.”

Bayles didn’t. A decade later he returned to the forests of the northern Sierras, Mount Shasta, and Redwood coast regions to create a photo exhibition that traveled through California and Oregon. In 2004 he expanded the project, focusing on how northern California’s logging industry had changed and altered the lives and culture of the men with whom he’d spent long days working in forests, men who worked with their hands and intuition. He discovered that with the increased industrialization of the forest and the arrival of machine-oriented tree felling, work that had relied on experience in meeting challenges, on camaraderie and trust, was in danger of becoming more like a robotically-operated assembly line. As one logger told Bayles, “They’re taking the Paul Bunyan out of logging.”

There’s a poignancy to these portraits and the stories they tell of changing times, hard times, and the humor found in between the dire risks loggers encounter every day. Bayles’ photographs and oral histories introduce us to men who love the forests in which they’ve spent, and sometimes risked, or lost, their lives. Many lament the unnecessary loss of trees and the advent of practices favoring quick profits over safety and sustainability. Bayles’ work is a testament and tribute to a fast-disappearing chapter of American woodsmen, one that may soon be forgotten.

—OSU Press 2023